“The” Customs Union, “a” Customs Union, and aligning tariffs with the Customs Union

The idea of the UK staying in the European Union’s Customs Union after we exit from the EU has once again risen into political discourse.

This idea is expressed in different ways. One way is for the UK to stay “in” the European Union’s existing Customs Union. Another way is for the UK and the EU to join together to form “a” customs union between them. Quite what the practical difference is between these two formulae is not clear. A third way it is expressed is for the UK to maintain its external tariffs in alignment with EU tariffs. Vague suggestions are made that this might only be “partial”, ie covering some sectors of goods but not others.

But all these formulae come to the same thing. They all involve us giving up our right to set and decide the tariffs which are applied to goods entering the UK from the rest of the world. But it is not just about tariffs. Customs also operate a vast range of non-tariff controls on goods, all the way from health and other standards controls on food to, for example, safety of children’s toys. In order to operate any of the variously desribed schemes, the UK would also have to apply this vast range of EU mandated legislation as well.

Others have already pointed out the issue of the increased costs for UK consumers if we were to stay inside the Customs Union as a result of being required to continue to levy high tariffs on many kinds of goods which are available more cheaply on world markets, particularly the kinds of goods where there is no significant domestic UK industry to protect and any producer benefit of the artificially high tariffs goes entirely to producers in other parts of the EU.

The economic arguments against staying in the EU Customs Union are important, but the political and constitutional consequences are even more profound, and seem to be completely ignored those who argue for negotiating to stay inside “the” or “a” Customs Union. As explained below, remaining in the EU customs union would have profound implications for the ability of the UK to govern itself as an independent nation, and would deprive it of the ability to decide its own laws over very wide fields of domestic policy extending far beyond customs controls themselves.

It would also prevent the UK from exercising an independent trade policy or concluding its own trade agreements with states outside the EU, and would inevitably result in the UK being subject to the continuing jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice (ECJ) over the interpretation and application of the common rules which regulate the customs union.

The reasons why these are the inevitable consequences of remaining in the customs union will now be explained.

What is the EU customs union?

The EU customs union is a system under which all the Member States follow a set of common rules in exercising customs controls over goods entering the EU from the outside. The core of this system of controls is the levying of tariffs and the imposition of trade quotas under the EU’s Common Customs Tariff; but the controls exercised by customs extend far beyond tariffs to a huge range of other matters, such as checking food for compliance with health standards and checking that consumer goods comply with safety rules (such as the rules limiting lead in children’s toys).

The very nature of the EU customs union requires that the common rules be interpreted and applied in a uniform manner by all Member States. If this were not done, it would result in goods entering the EU via the ports of a Member State with laxer controls and then circulating freely inside the EU into the markets of other Member States. Obviously, this cannot be tolerated under a system where no systematic customs controls are exercised on the flow of goods inside the EU between Member States, especially since importers might be tempted to “game the system” by diverting their imports into the EU to flow through the ports of a Member State where they had found a weakness.

If the weakness involves failing to impose tariffs in a uniform manner, that would have economic and fiscal effects in allowing lower-cost imported goods into the whole EU market; if the weakness is in safety or environmental standards the effects on consumers could potentially be very serious.

The European Commission makes no bones about the nature of the customs union on its website.

“About the EU Customs Union

The Customs Union is a foundation of the European Union and an essential element in the functioning of the single market. The single market can only function properly when there is a common application of common rules at its external borders. To achieve that, the 28 national customs administrations of the EU act as though they were one.

These common rules go beyond the Customs Union as such – with its common tariff – and extend to all aspects of trade policy, such as preferential trade, health and environmental controls, the common agricultural and fisheries policies, the protection of our economic interests by non-tariff instruments and external relations policy measures.

Today, in an era where terrorism and other serious crimes operate on a cross-border and trans-national basis, customs authorities are increasingly called upon to carry out non-fiscal tasks aimed at improving internal EU security. The customs are thus facing new challenges: they must ensure the smooth flow of trade while applying necessary controls on the one hand, and also guarantee the protection of the safety and security of the Community’s citizens on the other hand.”

The basics part 1: features of a customs union

The European Union’s customs union means that goods which come into the EU from outside are subject to a common external tariff, but once they have entered through an external port and paid any duty which is due on them, they can then circulate freely inside the customs union. And goods which are made inside the customs union can likewise circulate freely without being subject to tariffs at the internal borders within the customs union.

The main problem with a customs union is that it requires all its members to operate external tariffs which are identical. This means that each country of the EU must implement the common tariff even where that is contrary to its own economic and national interests. An example of that is that the UK has to levy high tariffs on many kinds of foodstuffs which are not grown in the UK, but are grown elsewhere in the EU mainly in Southern Europe. Even assuming for the sake of argument that tariff protection can be beneficial (a proposition strongly disputed by knowledgeable economists) it makes absolutely no sense to levy high tariffs on goods which you do not make inside your own country. This just drives prices to consumers up above world prices, but such benefits to producer interests as this tariff wall brings go solely to the benefit of producers in other countries elsewhere in the customs union.

The requirement that each customs union member must have the same external tariffs causes a further problem. That is that individual members of a customs union cannot negotiate trade deals with non-member countries which involve reductions or waiving of tariffs. The reason is that goods could then flow in from the non-member state with which the deal had been done without paying the external tariffs, and then circulate inside the customs union into countries who are not parties to the trade deal. Therefore only the customs union as a whole, and not any individual member state, can enter into any form of trade agreement involving tariff concessions with non-member countries.

The obligation for member countries not to conclude individual trade agreements with non-member countries has been embedded in the EU treaties since the original Treaty of Rome, which conferred “exclusive competence” on the European Commission to negotiate external trade agreements.

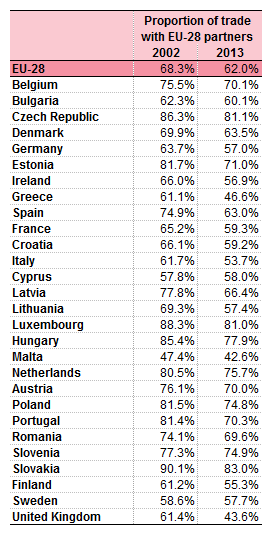

A further consequence of operating a customs union under the EU system is that it leads to collection of the tariff revenue into a common central pot. This is because when tariffs are collected at a port of entry, it is unknown where the goods will end up inside the EU and therefore which consumers in which country will ultimately bear the tariffs. This system of sharing of tariff revenue is particularly disadvantageous to the UK because it has the highest percentage of its trade outside the EU of any Member State:

Eurostat Table Intra-EU Exports by Member State

[Table published by Eurostat statistics office which shows that the UK has the lowest percentage of its goods exports inside the EU of any major Member State – 43%, compared with for example France at 59% and Spain at 63%. Further, the UK’s share of goods exports going to the EU27 declined from over 61% in 2002 to 43% in 2013, and is now even lower according to the latest (2016) ONS statistics.]

These figures mean that the benefits conferred by customs union membership in the form of freer flow of trade inside the customs union external wall are lower for the UK than for any other sizeable Member State (only tiny Malta has a lower proportion). And the negative impact of customs union membership on external trade with the rest of the world falls more heavily on the UK than on any other significant Member State.

It should be appreciated that the restrictions which apply on the rights of the individual members of a customs union are intrinsic in the very nature of a customs union. They cannot be negotiated away, or it ceases to be a working customs union.

For these reasons, there are not many customs unions in the world between substantial countries apart from the EU itself. There are quite a number of customs unions where very small states or territories form a customs union with a neighbouring or surrounding big state. But the more usual form of trading relationship between larger states is the free trade area.

The basics part 2 – free trade areas

Despite the fact that many people do not understand the difference between a customs union and a free trade area and tend to lump them together, they operate differently. A free trade area also achieves reduced or zero tariffs on trade in goods between its members. But it operates in a different way, which allows its individual members to operate their own differing external tariffs on imports from non-members, or indeed to conclude trade deals with non-members which provide for zero or reduced tariffs.

Free trade area agreements typically apply zero tariffs to goods which originate within a member, but not to goods from outside which are simply imported into and pass through another member of the FTA. This means that a country’s own tariffs are not subverted by goods from outside the FTA which pass through the ports of another FTA member. There is however an administrative cost, in that customs controls between the FTA members are needed to check whether or not the goods originate within the other FTA member according to “rules of origin”, and levy tariffs if they do not originate within the FTA. Such rules of origin controls are not needed inside a customs union.

The EU is itself a customs union, but it has free trade area relations with almost all European states outside the EU. The non-EU EEA States, Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein, have a free trade area relationship with the EU, not a customs union. This means that despite being inside the single market, they do have autonomy on external tariffs and therefore are able to operate an independent trade policy from that of the EU. Switzerland has a separate bilateral FTA agreement with the EU, and in addition has zero tariff arrangements between itself and Norway and Iceland via EFTA (which as its name implies is a free trade area and not a customs union). Most other European territories (apart from Belarus) also have FTAs with the EU.

So, whether to enter into a customs union or an FTA agreement involves a trade off between the administrative costs of operating rules of origin controls within an FTA, and the economic and political costs of being forced to operate inappropriate tariffs and not being able to conclude international trade agreements with non-member countries.

In the case of the UK leaving the EU, it is also obvious that the disadvantages of being in a customs union with the EU increase markedly once we cease to be an EU member. While we are an EU member, at least we have a vote in setting the common tariffs and in the EU’s attempts at negotiating and concluding external trade agreements. Once we cease to be an EU member, if we remained a customs union member, we would simply have to take and follow the EU’s policies on tariffs and external trade without having any effective means of securing that these would reflect our own interests.

Customs union – the control mechanisms

It is inherent in the nature of a customs union that there must be very tight harmonisation of the interpretation of the common rules. This is because a weakness in interpretation of the rules by one customs union member compared with others may well result in goods of the kind in question flooding in through the ports of the member which applies the weaker treatment and then fanning out throughout the customs union because of the lack of internal controls between customs union members.

This issue applies most obviously to tariffs, where even seemingly small differences in treatment (e.g. categorising certain goods within a lower tariff category) can have this kind of effect. If the customs union also applies to non-tariff customs controls such as technical standards or e.g. health checks on imported foodstuffs then those controls will also have to be harmonised in detail.

Within the EU, the harmonisation of the rules and of their interpretation is carried out at the first level by the European Commission which operates the common tariff (and special variations to the tariffs such as anti-dumping duties), and gives legal and administrative guidance to national customs authorities. At the next level, the interpretation of the common rules is carried out by the ECJ on preliminary references from courts and tribunals of Member States.

One example is Case C-338/95 Wiener SI GmbH [1997] ECR I-6495 where the ECJ was asked by the Bundesfinanzhof (German Federal Tax Court):

“Is the term “nightdresses” within the meaning of tariff heading 60.04 of the 1985 Common Customs Tariff, specifically tariff subheading 60.04 B IV b 2 bb, to be interpreted as covering exclusively “other” under garments which, in view of their characteristics, are clearly intended only to be worn as nightwear, or does it also cover products which, on the basis of their appearance, are intended mainly, but not exclusively, to be worn in bed?”

Despite a suggestion by the ECJ’s Advocate-General Sir Francis Jacobs that the Court might decline to rule on this question because it was so detailed and trivial, the Court did rule, apparently because it was essential for the ECJ to give this kind of detailed ruling for the proper functioning of the Common Customs Tariff across all Member States. In a 23-paragraph judgment, which included reference back to a previous case in which it had ruled that ‘pyjamas’ covered clothes mainly worn in bed as well as clothes only worn in bed, the ECJ ruled that the term ‘nightdresses’ in the Common Customs Tariff “must be construed as covering under garments which, by reason of their objective characteristics, are intended to be worn exclusively or essentially in bed.”

This apparently somewhat comic example illustrates how detailed needs to be the system of interpretation of the common rules of the EU’s customs union.

Being a member of the EU customs union outside the EU

The only major state which is not an EU member but is inside the EU customs union is Turkey. (There are also some micro-States, e.g. the Vatican and Andorra, in customs union with the EU). In fact, the customs union with Turkey is not complete since it does not extend to most agricultural goods.

The agreement between the EC (as it then was) and Turkey under which the EU-Turkey customs union operates is set out in a 1995 Decision of the EC-Turkey Association Council. Its provisions are extremely one-sided, as can be seen from its final Article on interpretation:

“Interpretation

Article 66

The provisions of this Decision, in so far as they are identical in substance to the corresponding provisions of the Treaty establishing the European Community shall be interpreted for the purposes of their implementation and application to products covered by the Customs Union, in conformity with the relevant decisions of the Court of Justice of the European Communities.”

Turkey is required to “align itself with Common Customs Tariff” (Article 13(1)) and also to “adjust its customs tariff whenever necessary to take account of changes in the Common Customs Tariff” (Article 13(2)). Turkey has no right to be involved in the EC’s decisions on changing its Tariff, but under Article 14(1) is to be “informed” of such decisions “in sufficient time for it simultaneously to align the Turkish customs tariff on the Common Customs Tariff.”

More generally, Article 56(1) says:

“1. Where it adopts legislation in an area of direct relevance to the functioning of the Customs Union as defined in Article 54 (2), the Community shall immediately inform Turkey thereof within the Customs Union Joint Committee to allow Turkey to adopt corresponding legislation which will ensure the proper functioning of the Customs Union.”

Similar provisions require Turkey to adopt EU Regulations and ECJ case law in the area of competition law (Article 39(1)(a)).

Turkey of course has no vote on such legislation, merely a right to have Turkish experts “informally consulted” on occasions when Member State experts are consulted (Article 55(1)).

Regarding trade with non-Member countries, Turkey is required by Article 16 to harmonise its commercial policy (i.e. trade deals with non-EU countries) with that of the EC. Thus Turkey is obliged to grant tariff free access to goods from a country with which the EU has negotiated a free trade agreement, without having a vote or a say in the negotiations.

However, this does not mean that Turkey will then necessarily get tariff-free access for its goods into the market of that non-Member state. That is dependant (Article 16(1)) on Turkey being able to negotiate a parallel trade agreement with that non-Member state.

Nor can Turkey negotiate its own free trade agreements with non-Member states. Doing so would breach the requirement to align its tariffs with the Common Customs Tariff.

For these reasons, the Turkey/EU customs union agreement has been compared by critics to the Capitulations of the Ottoman Empire, under which traders from Western countries entering the Ottoman Empire were exempted from local prosecution, local taxation, local conscription, and the searching of their domicile.

The manifest inequalities in the relationship between Turkey and the EU under the customs union agreement has led to a World Bank Report. Its recommendations have not been implemented.

What about a UK-EU post-exit customs union?

It might be argued that Turkey was in a weak position to negotiate an agreement with the EU and the grotesquely one-sided nature of the agreement therefore might be corrected in a UK-EU deal where the UK would have more bargaining power. Leaving aside the political question of whether the UK would really have greater bargaining power if it were to seek to maintain itself inside the EU customs union after exit, it is worth examining the practical question of whether it would be realistically possible for the EU to agree a less one-sided arrangement and still maintain the integrity of the customs union.

The problem is, that for the reasons already explained, it is not possible to operate a customs union in which the individual members are allowed to diverge in tariffs or in the myriad of other matters subject to customs controls. Such divergence is simply not something which the EU is in a position to negotiate or agree to.

This leads on to two further very serious problems.

One is the issue of future changes to the rules of the common customs union. If the EU in future modifies or adds to those rules, a mechanism has to exist to maintain the application of harmonised rules at the frontiers of the customs union. That then entails an explicit one-way obligation to follow the EU (like Turkey) or a disguised compulsion to follow (like under the EEA Agreement where EEA members are effectively forced to follow changes made by the EU to internal market rules without being allowed a vote on them).

The second very serious problem is the impact of the customs union on the ability of the non-EU member of the customs union to conclude trade agreements with third countries. It would not be able to agree FTAs involving zero tariffs on goods from a non-Member country because those goods would then enter and circulate round the customs union and avoid the tariffs which would be applicable if they had been sent direct from the third country to an EU state. The sanction for operating such a non-EU FTA would be the reimposition of rules of origin controls on goods flowing from the non-EU state into the EU. Turkey has been deterred by this consideration from entering into any FTAs, other than FTAs which parallel the EU’s FTAs. To add insult to injury, Turkey is obliged to permit the import of goods from the EU which enter the EU tariff-free under an EU FTA with a third country, even where Turkey is unable to obtain an FTA with that country to permit the tariff free export of its own goods there.

Since the EU customs union extends beyond tariffs and applies to many other matters, the need to follow future changes in EU rules applies equally to non-tariff controls. For example, it would not be possible for the non-EU member to enter into an agreement with a third state under which that third state’s technical standards or e.g. food health controls would be recognised as compliant for imports to the UK, if those differed in any significant way from the common EU standards and controls.

It is also difficult to see how the UK could then diverge from these standards in its internal law if were to wish to do so.

Given that in third country trade talks the Department for International Trade would be unable to offer either concessions on tariffs or concessions on a wide range on non-tariff measures embodied in common EU customs rules, it is very difficult to see what it would have to offer our prospective trading partners in return for enhanced access for our goods and services to their market and therefore how any meaningful trade agreements could be concluded.

Harmonisation and sovereignty

The fundamental problem is that a system where all countries must closely follow a set of common rules (including future changes to them) and must interpret and apply them in a uniform manner necessarily severely curtails the internal and external sovereignty of customs union members. While we are EU members it can be argued that this is an area where sovereignty has been shared, in that we have a vote on these matters and have representation on the ECJ. This would cease on exit, and the argument that sovereignty had been “shared” would no longer apply.

It seems unlikely that the EU would be willing to agree anything other than a system under which the EU gives and the UK takes, if the UK wishes to remain inside the customs union. In theory, there are the following possible mechanisms for maintaining a harmonised approach:

(1) Explicit subservience, in which the non-Member state explicitly adopts and follows ECJ interpretations of the common rules and also probably administrative decisions and opinions by the Commission;

(2) Disguised subservience, in which the non-member state follows rulings of a body which is nominally independent but in practice will follow ECJ rulings. This is the model under the EEA Agreement, where the so-called EFTA Court in practice follows the ECJ. While in theory under the EEA Agreement it is entitled to depart from post Agreement ECJ rulings (although not pre-Agreement rulings which it must follow de jure) in practice it always follow the ECJ even to the extent of reversing its own jurisprudence where it has decided a point in advance of an ECJ decision on it. The further problem with this model is that as a fall back if there is a failure to ensure interpretation consistent with the ECJ, then the EU can declare the Agreement non-applicable to the sector concerned. In the context of a customs union agreement (which the EEA is not) this would entail the re-introduction of customs controls including rules of origin or even imposition of tariffs in the event that the non-Member state were to depart from ECJ rulings.

(3) Higher neutral court. This model would involve the harmonisation function being performed by a higher level court or body which has power to rule on both the EU and the non-EU member states. This model would not provide independence of action but a degree of co-decision comparable to current EU membership. While in theory this might mitigate some of the serious imbalance and loss of sovereignty for the non-member State within the customs union, it seems fanciful to suggest that the EU would accept such a solution at a political level, and even in the unlikely scenario that such a scheme were politically agreed, it would be very likely indeed that the ECJ would rule that the resultant agreement was incompatible with EU law and with the exercise of its own powers under the Treaties.

Conclusions

Staying inside the EU Customs Union after ceasing to be a Member State would necessarily entail a severe and continuing curtailment of the UK’s powers to govern itself as an independent state and would subject it to the continuing effective jurisdiction of the ECJ. In particular:

1. The UK would be obliged to operate a system of external tariffs according to the Common Customs Tariff decided by the EU, and would be obliged to follow future changes made to the Common Tariff, while not having a vote on those changes.

2. The UK would not be allowed to enter in to trade agreements involving reduced or zero tariffs with non-Member countries, which would make it in practice impossible to conclude meaningful trade agreements. It would in practice be obliged to follow the terms of trade agreements reached by the EU with non-Member countries or blocs, without having a vote on those agreements or on how they are negotiated. It is hard to see what useful purpose would be served by having a Department of International Trade.

3. The UK would be obliged, either directly or via an indirect mechanism similar to that of the EFTA Court under the EEA Agreement, to continue to be bound by past and future decisions of the ECJ on the interpretation of the common rules of the customs union.

4. If (as seems inevitable) the continuing customs union with the EU extends to non-tariff customs controls (such as certification of compliance with technical or safety standards, health requirements for food, etc) the UK would be obliged to follow the EU’s future rule changes on all these matters as well as interpretations of the rules by the ECJ.

5. The UK would have to apply these same rules and regulations across its own domestic economy as well. WTO rules do not permit us to operate different or more stringent standards on imported goods than the rules under which we allow goods to be put on our domestic market.

5. Having to follow the EU’s common rules on such non-tariff customs controls would (1) mean that the UK would be unable to negotiate changes to such controls with non-Member countries in order to facilitate trade with them and (2) make it in practice very difficult indeed for the UK to change its own rules for goods in its domestic market to differ from those applicable to imported goods under the Customs union common rules.

6. Overall, the UK would be significantly worse off than it is at present as an EU Member because it would be bound by the common rules of the EU customs union over wide areas of policy, be unable to operate an international trade policy independently of the EU, but have no vote on these matters.